Beginnings

Not that long ago, I believed with all of my being that my heritage was German, Swedish and French, and that my great-grandmother was a Cherokee princess descended from Pocahontas. When my son, who rarely displays an interest in anything besides video games, said he’d like to take a DNA test, I agreed. Always good to encourage the kiddo’s interest, and his father’s Baltic and Native American roots were likely to be much more interesting than mine.

So we all took swabs — Caleb, my parents and I — and waited for the results.

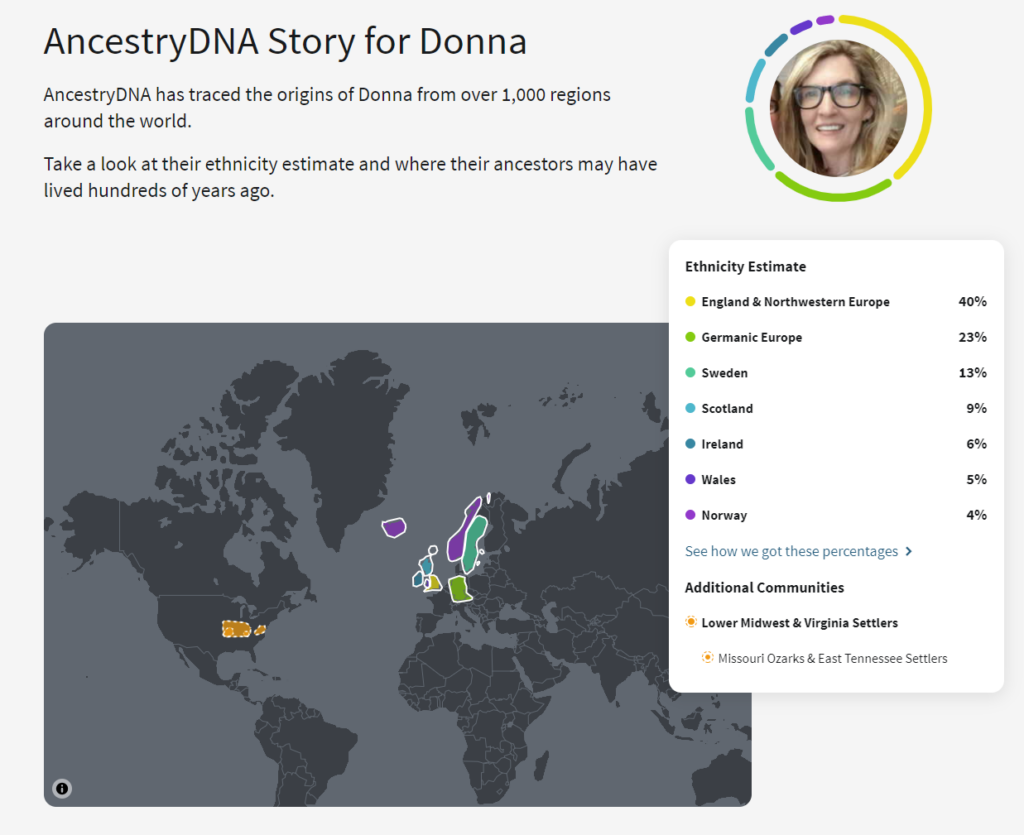

A few weeks later, my beliefs crumbled. I’m British? I’m not Native American? This couldn’t be right! This test must be a joke. (Caleb’s results came back largely as expected, although he didn’t have any Native American in his admixture either.)

Determined to prove that I knew more than a silly blood test, I signed up for a trial of Ancestry.

Three days and 72 sleepless hours later, I had close to a thousand people in my tree. I was descended from Kings and Queens! I am ROYALTY! I hadn’t yet learned about source documentation, and didn’t know that other trees were often inaccurate. I cut and pasted and connected and found out that what I thought I was didn’t matter at all because what I am is REALLY important. My German and Swedish ancestry (which did show up in my admixture) was a “brick walls,” a term I quickly learned and rue to this day.

As it turned out, much of that original research was incorrect, and several years later, I’m still finding my own errors.

But what do you know? I’m western European, mostly British. I really am. The vast majority of my ancestors immigrated to the United States in the 17th and 18th centuries. I’d heard my mother speak of theTrigg family, and it quickly showed up in my tree. A US Congressman? A friend of Thomas Jefferson? She never told me that! My paternal grandfather’s family was early Dutch settlers of New York, the Wynkoops. I always thought he was 100% German, and his father’s family was indeed German, immigrated in the mid-1800s, but all records stopped on this side of the pond. Similar with my Swedish great-great-grandfather, whose census records variously claim he came over in 1852 or 1849, and that his name was Johnson or Johansson or Swanson or Svensson, documentation that I can begins in the United States. The lesson there — I had believed in the heritage of my most recent immigrants, whose heritage was known. But once the veil was lifted, there was far more British and Irish than I would ever have believed had I not discovered it myself. Notable is that I have only two immigrant ancestors who arrived after 1800. While not exactly a blueblood, my family has its roots in colonial America, I’m largely a Virginian, and daughter of the American Revolution at least a dozen times over.

As for the Native American, my mother to this day tells people she is descended from Cherokee royalty. But it’s just not there.

Many years later, genealogy has become my passion. I’ve travelled the US seeking information in dusty courthouses and remote genealogy rooms. I’ve made one the best friends of my life; and, yes, she’s a cousin. It doesn’t matter where I came from, but rather what I came from. I’m a Southerner, and a Quaker, and a compilation of all those who preceded me. I am uniquely me because of them. So many family traditions make sense to me now. They didn’t appear in isolation; they came from where WE came from.

And I can still spend three sleepless days at my computer seeking out more information about my family, only now I’m devoted to accuracy.

.