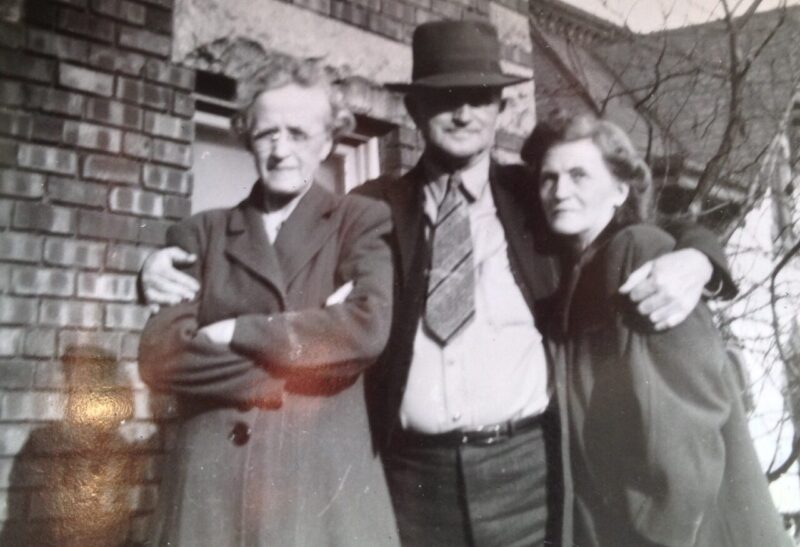

Favorite Photo

My Grandparents’ 25th Wedding Anniversary, September 1965.

I was the first child and the first grandchild. We gathered in the “North Room” of my grandparents’ home for this photo, my grandparents, my parents, my dad’s brother Tom and his wife, Roseann, and me. For the anniversary party, everybody dressed up, and there had been guests, and cake.

I would turn one year old in a few months.

My grandfather, George Frederick Malter, Fred, my Papa, was the finest man I’ve ever known. He was a gentleman farmer who wore coveralls in the field, but never went to town without a hat and a clean shirt. He was kind, a man of his word for whom a handshake carried the weight of a written contract. He spent long days in the fields, but also served on the Board of Trustees at the local bank. He was frugal and invested wisely, tall, strong, and proudly German. (His father still spoke the language to relatives in Hermann, Missouri.) My grandfather was always smiling. In my earliest memory I’m riding on a John Deere lawnmower, sitting on my grandfather’s lap.

He had a big vegetable garden and he was deathly allergic to bees. As Thomas Jefferson said, “It’s amazing what you can accomplish if you are always doing.” My grandfather was always doing. I grew up in a small farmhouse next to my grandparents’ home, and remember cursing Papa early Saturday mornings when he was out on his big tractor grading the country road to our house at 5 AM. During the depression, he’d driven a milk truck for a nickel a day. He never missed going to the Malta Bend Methodist Church on Sunday mornings, maybe at my Grandmother’s insistence, but he didn’t sing the hymns. He occasionally drank a beer. He told us he’d always wished he’d become an architect, but he never complained about being a farmer other than the typical worries about the weather. He called me “presh,” short for precious.

My grandmother epitomized matriarchy. She never hesitated to show disapproval, but was equally effusive in her praise and love. She played bridge, studied her Bible and volunteered to raise money for the church. She had been born Catholic but converted to Methodist as a child. Devoted from a young age, the Methodist Church was closest to her home and she wanted to go to church, so she walked there, alone.

After she married and had her own family, on Sundays after church, she always cooked grand Southern lunches for her children and grandchildren, often fried chicken finished with pineapple pudding, all of us gathered around the dining table of their home, where we said grace before anyone touched his plate.

Nanny cared for me as a child while my mother finished college. She let me play dress-up in her beautiful (often hand-sewn) dresses and costume jewelry. Until her death last year at age 98, she went to the beauty shop every week and was always beautifully attired. As a girl, she loved the movies and she loved to dance. She’d grown up during the depression, the daughter of a widowed mother and sister to two brothers who went to war. When she was three years old, in 1925, her father drowned in the Missouri River after his boat overturned. Her mother cleaned houses to support the family during the Depression. My grandmother never owned a new garment until she married my grandfather, and she worried about money until the day she died. But she loved to order geegaws she found in catalogs and saw on QVC. Maybe she just liked seeing the UPS man drive down her country lane to bring her a little treasure in a box.

The family of seven in this photo grew to ten with the addition of my two cousins and my sister Leslie, the baby of the family. Nanny liked game shows (except Cash Cab!) and word search puzzles and telling off-color jokes. She loved butterflies.The sole driver among the women of her generation, she chaufferred her sister Virginia Stockman Ricks (“GeeGee”) and Papa’s cousin Catherine Rennick to get their hair done and have lunch. She never drove her big Ford Sedan outside the boundary of Saline County.

My grandparents lived in an antebellum home on the family farm, a century farm, which means it has been in the family for more than 100 years. The house sat at the end of a gravel road about a mile from the highway and three miles outside Malta Bend. Legend was that a solder had died in the hallway during the Civil War. As a child, I was terrified of the basement, but in later years fascinated by the construction of the house. The boards were held together with wooden pegs instead of nails, and those pegs had held the house up for nearly 200 years. I remember visiting them next door in the evenings where they sat on their recliners watching television. They never missed Lawrence Welk. I was welcomed with hugs and smiles and they always turned the volume down to talk with me. My grandparents travelled, Aruba and Hawaii and Las Vegas, always returning with small gifts for the grandchildren. When my father played college basketball in the 60s, they followed him all over the country to watch his games. As they grand-children grew, they attended their games too. They were doers, and goers.

I was fortunate to grow up in a small town (population 232, Salute!), surrounded by extended family. Papa and his brother farmed together, until their families expanded and they had sons to get started in the family business. My grandparents had both grown up in Malta Bend, as had their parents. Malta Bend is a footnote to the Journals of Lewis & Clark, the original home of the Missouri native American tribe, where they they passed on June 4, 1804. At one point, Malta Bend had once been a bustling small town, but during my childhood, it was just a stoplight on the highway with a small general store, the Zip Dip diner and a couple of gas stations.

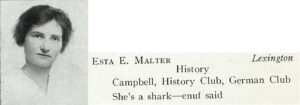

Most kids stayed in Malta Bend and had kids of their own. Cousins were firsts and seconds and even thirds and beyond. My mother and I visited Esta Nye, my great-grandfather’s sister, born in 1887, the youngest daughter of German immigrants who came to the United States in 1853. Aunt Esta graduated from Warrensburg State Normal School in 1917 with a degree in history.. Her college yearbook says “She’s a shark — enuf said!” Not enough said, because I have no idea what it means. Esta’s husband Les Nye was a master craftsman who hand-made beautiful wooden furniture. Her father, Thomas Malter, was said to have been born on the ship coming over from Germany. Family lore claimed the ship’s captain had wanted to adopt him.

I left the farm as soon as I could. I hated being labelled a farm girl, a “hick,” and spent the next several decades trying to appear less provincial. It was an affectation, of course. You can take the girl off the farm … Looking back now, I realize I had the ideal childhood.

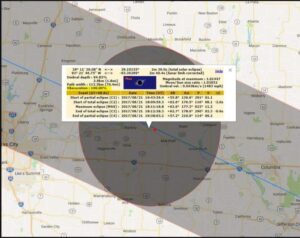

In 2017, we gathered for the total solar eclipse. Our century farm was just a few hundred yards from the line of total totality. We watched the sun disappear while the leaves danced in shadows. My grandmother put on her spiffy clothes and wore her special glasses and made goofy faces for the camera. She was 97 and still lived independently in the big farmhouse. It was the last time we were all together there, all of us except my grandfather who had died in 1996, rest in peace.

This photograph is my favorite because it, literally, represents the world to me, my family, the love, the pride, and the loss. My grandparents were younger than I am now; my parents were young enough to be my children. We had no idea what lay ahead, and we smiled with only a little reserve, because the possibilities were endless. Our future as a family was even better than anyone could have imagined. We had no tragedies or dramas, not even divorces, and my grandparents were healthy into old age. Still, there was not enough time. I’m so glad we captured this moment at the beginning of mine.

My Namesake: Louisa Jane Orr

I was named after my father Donald Frederick Malter. I could tell you about my father, but it might comprise a book, and its last page is far from written.

My middle name is Louise. As I was pondering the prompt "Namesake," I realized how little I knew about my Aunt Louise, except that she was the elder sister of my great-grandmother Adra Olive Orr after whom my mother Olive is named. I remember Grandma Adra, but I was born two years after Aunt Louise died and I don't recall anyone ever talking about her.

A little research revealed that she was, in fact, named Louisa Jane Craven, nee Orr, that she died in 1962 in Kansas City, that she was divorced, and that she was a retired bank teller. It was a start. What is a life, really, after you're gone, but the memories of those who shared an overlapping fragment of your moment in time? So many deceased ancestors exist only in digitized text and maybe a photo with their names lovingly scrawled on the back. I am fortunate to have living relatives who remember my Aunt Jane, and I was able to call them for more information.

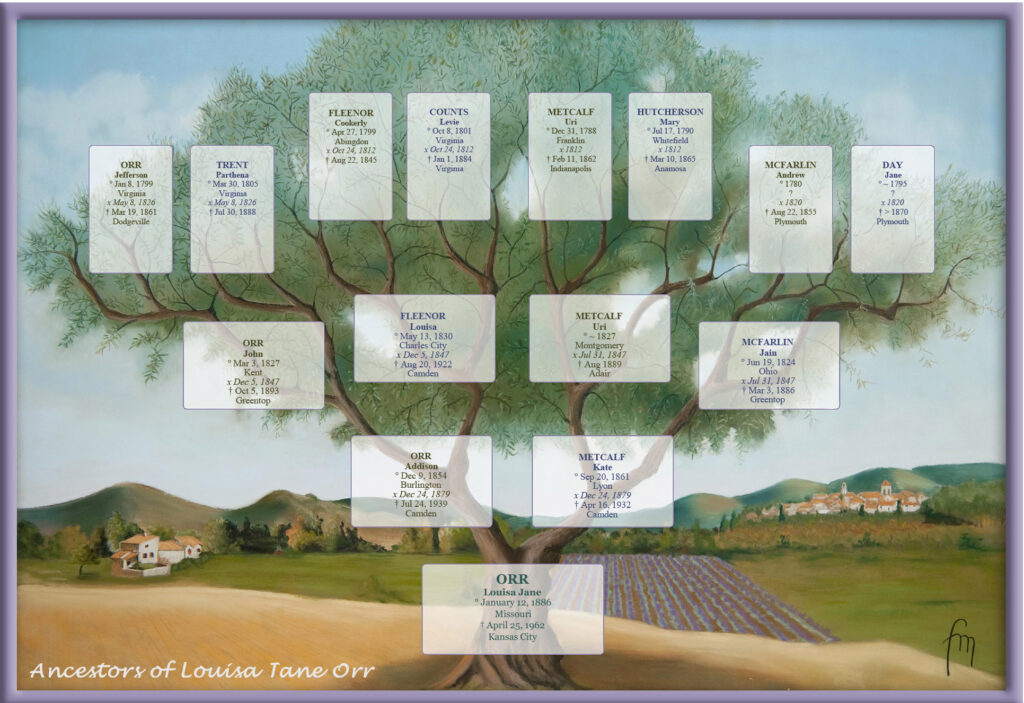

Louisa (loo-EYE-zah) Jane Orr was born on January 12, 1886, in Bevier, Missouri, the daughter of Attison (or Addison) Milton Orr and Katherine Olive ("Kate) Metcalf.

Although she may not have known it, Louisa came from a lofty family line: through her paternal line, she was descended from Christopher Branch Jr., who was also the great grandfather of Thomas Jefferson, making her a 3rd cousin thrice removed of my favorite Founding Father. (Orr >> Trent >> Branch)

Louisa even had royalty in her veins. Through her maternal line, her 7th great-grandfather Robert Abell immigrated in 1630 from Derby, England, to Weymouth, Massachusetts. Robert Abell is a "gateway ancestor," the alphabetical first in a list of early American immigrants whose line of ascendancy can be documented back to Charlemagne. Charlemagne, Charles I, was the King of the Franks from 768, the King of the Lombards from 774, and the Emperor of the Romans from 800. During the Early Middle Ages, he united the majority of western and central Europe. He was later canonised by Antipope Paschal III. (As exciting as that sounds, it is estimated that nearly three-quarters of Americans who can trace their lineage to Colonial America are also descended from Charlemagne. Dude was prolific! See also "Am I Related to Royalty?") (Metcalf >> Abell >> Charlemagne)

But that's all a far cry from Greentop, Missouri. Louisa's maternal great-grandfather Uri Metcalf Sr. had moved from Massachusetts to Ohio to Indiana (where he was the first blacksmith in Marshall, Indiana, in 1820) to Illinois to Iowa, following land grants, and never very successfully. There were lawsuits and foreclosures. Uri Sr. had been President of the Illinois Abolitionist Party. At age 72, he enlisted to fight for the Union against slavery, and he died ten days later of a stroke while training in Indianapolis. He may not have been much of a businessman, but he obviously had a strong moral compass and was willing to die for what he believed.

Louisa Jane's grandfather, Uri Jr., moved to Greentop from Iowa to open a woolen mill which was later the site of the first union strike in the state of Missouri.

Louisa's father, Attison Milton Orr had come to Greentop as a child, also from Iowa, between 1860 and 1870. He was a farmer, and married Kate Metcalf on December 24, 1879 at her parents' home. Attison and Kate had their first child, Andrew, in 1880, followed by Leila, Louisa and finally, seventeen years later, my great-grandmother Adra. There were other babies, at least four, who died as infants. Louisa was named after her paternal grandmother, Louisa Fleenor, who had come to Missouri from an esteemed (and prolific) Virginia family, to marry John Williamson Orr.

I don't know anything about their childhood, but based on newspaper clippings and later obituaries, they were a close and prosperous family, religious and hardworking. The girls learned to sew and to cook (Southern traditions passed down to me) and were regular church goers.

In 1903, Louisa's 21 year-old eldest sister Leila died, allegedly from a flu epidemic, although I can't find any reference to an epidemic that year. Her funeral was well attended by family members who travelled from St. Louis and as far as Indiana. Leila's obituary mentions that she was a faithful member of the First Baptist Church.

Louisa graduated from Bevier High School the next year, in 1904. Shortly thereafter, the family moved to Camden, Missouri, where Attison worked as a carpenter. Camden, according to The History of Ray County, Mo., was "situated on the north bank of the Missouri river, on the Wabash, St. Louis & Pacific Railway, five miles west of Richmond and Lexington Junction, and six miles southwest of Richmond, was incorporated in May, 1838." In 1910, Camden had eight stores, two hotels, two school houses, one church -- owned and used by all denominations -- and one large flour mill. It also had a coal mine. It is unclear why they made the move, but I'm sure the loss of a child weighed on their decision, and perhaps better opportunities awaited in a larger town.

In 1911, on December 23, and at the age of 25, Louisa married Erwin Elwood Cravens in Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. His draft registration card lists him as tall, blond and blue-eyed, which makes sense because my Aunt Louisa was a tall woman herself, nearly 5'10". She may have became an expert milliner and seamstress because if she wanted lovely clothes that were long enough, she had to sew them herself.

Two years later their daughter Marjorie was born. (Marjorie's name is variously listed on censuses as Margaret and Margarite.)

My Aunt Louisa, called Jane to distinguish her from grandmother Louisa who still lived with the family, was a rare high school graduate (the school in Camden ended at grade eight). She found work as a bookkeeper, managing the accounts for coal mine's company store. Her manager at the store was Albert Sydney Johnson, my great-great-grandfather who had immigrated from Sweden as an orphaned teenager in the 1860s. His son, the handsome and affable coal miner Olie Johnson, married Louisa Jane's little sister, my great-grandma Adra, on December 23, 1916. My grandmother Beverly came along in 1917, and her brother Andrew in 1921.

By 1920, Louisa Jane and Marjorie were living with her parents in Camden. Their home had the first kitchen cabinets in Camden, built lovingly by hand by an aging Attison Orr. It was a large, extended household. Louisa's grandmother Louisa Fleenor lived with the family until her 1922 death in Camden at age 92 years, 8 months. By this time, Erwin had gone to Kansas City to work as a lineman and was living in a boardinghouse. On the census, he listed his marital status as "Married" but she was, oddly, "Widowed."

The company store existed on the bluffs of the Missouri River and became a family gathering spot. My grandma Beverly told me that she had learned to drive in the truck owned by the coal mine, and that she made deliveries for the company store as soon as she could reach the pedals. At age ten, she had to pay a few cents to get a driver's license -- no test, just a small fee, and she became a commercial driver when she could barely reach the pedals. Aunt Jane had enough money to purchase a piano and lessons for her daughter Margery. Margery then taught my Uncle Andrew, eight years her junior, everything she had learned. Uncle Andrew was a dear man, a devout Christian, and a talented (and committed) piano player his entire life.

The Missouri River was a major means of transport and recreation, then as now. My Uncle Andrew recalled seeing the vaudeville comedian Red Skelton floating past the company store on the bluffs of the Missouri aboard the Goldenrod riverboat. This inspired him and my grandmother to put together their own vaudeville act in their teens. The Goldenrod itself later inspired the Oscar-award winning film Showboat.

The depression hit Camden hard, as manufacturing and coal mining virtually ceased. The Orr/Craven family was so poor that they couldn't afford feed for their chickens, but they were more fortunate than most. A monied family benefactor from Indiana moved to Camden and helped them purchase food, clothing and other essentials, but there was never enough. Health declined from lack of nutrition. Louisa Jane's mother Kate Orr died in 1932, followed by her father Attison in 1939.

Sometime in the mid-1930s, Louisa Jane and Marjorie moved to Kansas City to live with Erwin, where they rented a house on East 31st Street. Erwin worked for Ford Motor Company and Louisa got a job with the Federal Reserve. They must have been doing reasonably well as the rest of the nation recovered from the depression. Marjorie married and had Louisa's only grandson, Michael Jones, in 1933.

Early in the 1940s, my grandfather Olie Johnson, the affable Swedish coal miner, took a job with Butler Manufacturing in Kansas City, and moved from Camden into the Wells Apartment at 612 E. Ninth St, which my Grandma Adra managed. Aunt Louisa Jane left her husband and moved into an apartment in the Wells, from where she could easily walk to her job at the Federal Reserve. I don't know why they divorced, but I'm told that the women in my family have a habit of choosing bad partners and when they finally leave them, nobody ever talks about it. This is clearly another family trait that I inherited.

This is really where the story of my namesake begins, as this is the era of living, breathing memories. Louisa became the Aunt Jane of their memories. My mother recalls being a child in the early 1950s, running back and forth between her grandparents' apartment and her Aunt Jane's down the hall. In one of her earliest memories, Aunt Jane made her Rice Krispy treats in an 8X8 pan, the first she had ever tasted and "the most delicious thing" she'd ever eaten. Cousin Adra recalls a threadbare sofa where she slept in Olie and Adra's apartment, and the Murphy bed in Aunt Jane's smaller apartment where Aunt Jane slept. Aunt Jane taught her to sew clothes for her dolls, and took her to the Emery Bird department store, paid to have her photo taken with the "real" Santa. It was an expense her parents could not afford. Aunt Jane dressed beautifully and wore fancy hats that she made herself.

In 1952, at the age of 66, Aunt Jane filed for social security and likely had a comfortable pension from her time at the Federal Reserve. She stayed at the Wells until she could no longer walk up the stairs to her apartment. Around 1960 she moved to Armour Oaks Memorial, where she lived until her death on April 26, 1962 from respiratory failure. She is buried at Mt. Moriah Cemetery in Kansas City.

I see myself in Aunt Jane. I'm tall like her, and I have her long face and nose, strong cheekbones with a square, masculine chin. I am independent, good at numbers, a single working mom. I'm proud to be her namesake, wish I'd known her but with thanks to those who shared their memories, I know much more than I did last week.

Family Legend

I wish I had a unique legend but, like about half the genealogists I know, there is a Native American in the woodpile. A good number of people I know are flabbergasted to learn that they’ve been hoodwinked by family lore.

According to my mother, for as long as I can remember, my great-great-grandmother was said to have been half Cherokee, a granddaughter of Pocahontas.

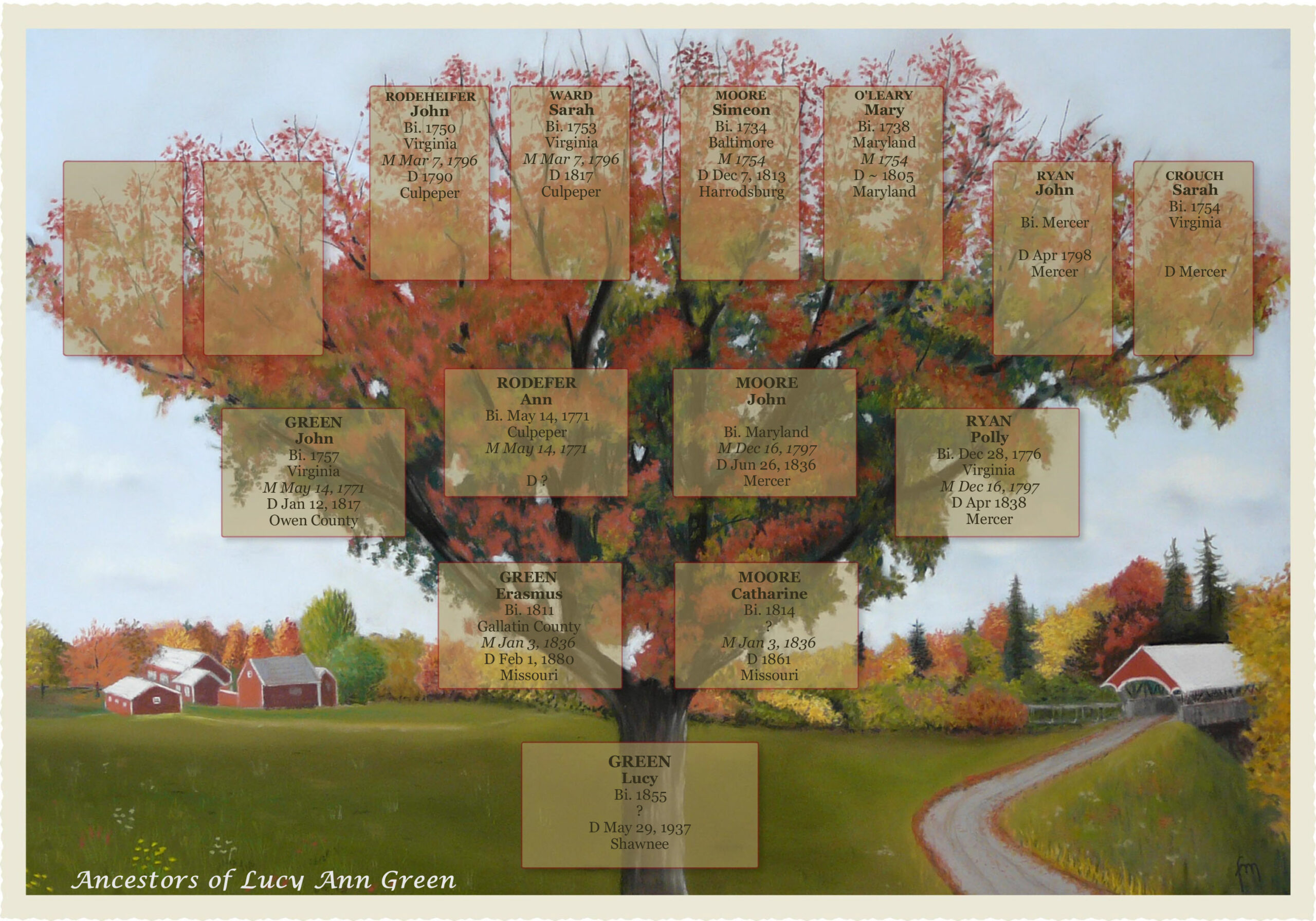

Her name was Lucy Green and she lived in Shawnee, Potawatomie, Oklahoma, and she ran a restaurant. And one of,her parents was a Cherokee. That’s all we knew.

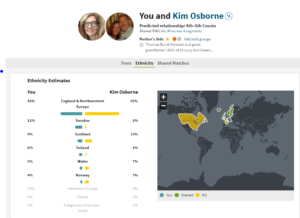

I met my cousin Kim while hunting for Lucy Green. Kim had been adopted at birth and was using her DNA to find her biological family. Kim and I were connected in a Lucy Green circle on Ancestry, along with my mother, and one other person. I sent Kim a message and asked if she knew anything about Lucy Green. When she told me her story, it quickly became apparent that Kim knew less about Lucy Green than I did. We did figure out that we were third cousins: her great-grand grandfather Henry Doniphan Hewlett and my great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Hewlett were siblings, born in Ray County, Missouri.

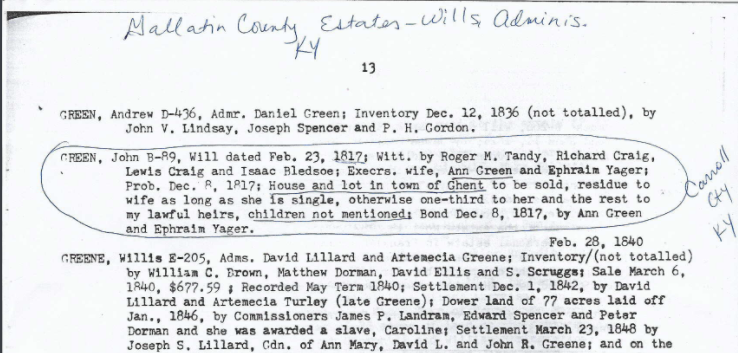

Kim and I started sharing what bits and pieces we’d discovered in our research. Although Lucy appeared on a lot of Ancestry trees — she had six children who survived to adulthood and each of whom also had numerous children — not one of the Lucy Green trees had verifiable ancestral lines. We believed that Lucy was born to Catherine (no last name) and Erasmus “E.H.” Green in Mercer County, Kentucky.

Kim and I lived closed to each other and decided to meet at the Midwest Genealogical Center in Independence Missouri. The Genealogical Center is the nation’s largest public genealogy library. I had never been there before — or to any genealogy lilbrary — but Kim was an old pro.

We started looking at marriage records in Mercer County, Kentucky, and fairly quickly found one Catherine Moore’s marriage to Erasmus Green, signed by Sarah Moore. We also found Catharine’s sister’s marriage record within the same time frame. And we discovered that her father, John Moore, had died shortly before her marriage. But about John, we knew nothing. Was he an American Indian? Kim didn’t think so, and I was becoming more skeptical by the minute.

My mother had always told me that the family lineage to Pocahontas was contained in a family history book written by Jean Hamacher and housed at the Ray County History Museum. Of course that was our next trip.

I’d been to the Museum previously with my mother but the library had been closed that day. Kim and I dug into the stacks and found a bound book authored by Mrs. Hamacher. The book was actually about the Hewlett family that Lucy had married into.There, in one small paragraph, it said “Family legend says that Lucy’s father, Erasmus Green, was descended from the Cherokee tribe, but this author has found no evidence of that statement.”

Wait, THAT was the incontrovertible evidence to which my mother had referred? It was … nothing.

The day turned out to be fantastic nonetheless. We made a trip to the Courthouse and dug through the real estate records to see where Erasmus and Catherine had lived. We found the original land grant, and a number of transfers to Erasmus and later his children. We found Erasmus’s Last Will and Testament, unlikely to have been touched since he died in 1890. (His estate was worth a little less than $7.)

The very kind and patient County Assessor looked at a little hand-drawn map we had and used images from Google Earth to identify the tract. We found Erasmus’s farm about ten miles north of town, with a barn that looked like it had existed in Erasmus’s time. The property was surrounded by overgrown trees and cluttered with rusted old trucks. It didn’t look like a friendly place, but it was where we began.

But … back to my legend.

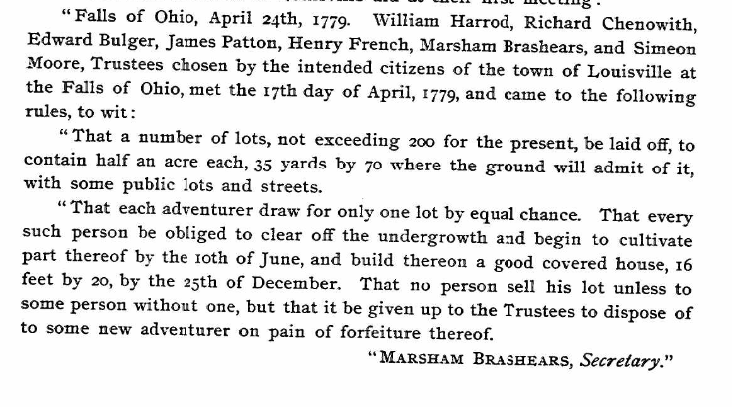

One day on Ancestry, I ran across a tree that said Catherine’s father was John Moore, born in Maryland. This information was different than anything I’d ever seen before. I contacted the user and the floodgates opened. She had actually been to Mercer County, Kentucky and had unearthed the mysterious John Moore.She provided me with his Revolutionary War pension record. John had been revolutionary war soldier who had been captured by the Indians, and kept captive for three years. John Moore knew the native language because he’d been constantly threatened with Indian attack growing up on the frontier in Maryland. During his captivity, John was tasked with serving as an interpretor between the Natives and the British. He he arrived in Harrodsburg with his father, Simeon Moore, and Daniel Boone. Simeon’s sister had been married to James Harrod. John’s ancestry? Not Native American.

Was it possible that the legend arose due to John’s capture by the Native Americans? That’s possible But if Jean Hamacher’s notes are correct, the Pocahontas line ran through Erasmus, Lucy’s father.

I’m still working on him. He’s my brick wall. His father, John Green, was raised in Culpeper, Virginia. At the time of his birth, there were no fewer than twelve “John Green”s in Virginia, and mine doesn’t fit into any of the known family trees, But it’s fairly safe to assume that John Green was somehow related to the Duff Greens who immigrated from Scotland in the late 1600s, and very unlikely to be a Native American.

My mother refuses to trust my research. Her Aunt told her we were Cherokee, and by golly, we’re Cherokee. I have another cousin who visited our Oklahoma ancestors in the late 1960s, and she swears they were living on the reservation. I can’t hold anything against Elizabeth Warren. She had no reason to disbelieve her family lore either.

Whenever I make a genealogy trip, my mother’s first question is always “Did you find the Indian?” I sent her this photograph from the Kentucky Museum of History. It’s the closest I’ve come.

Continue to Part 2. Pocahontas.

Beginnings

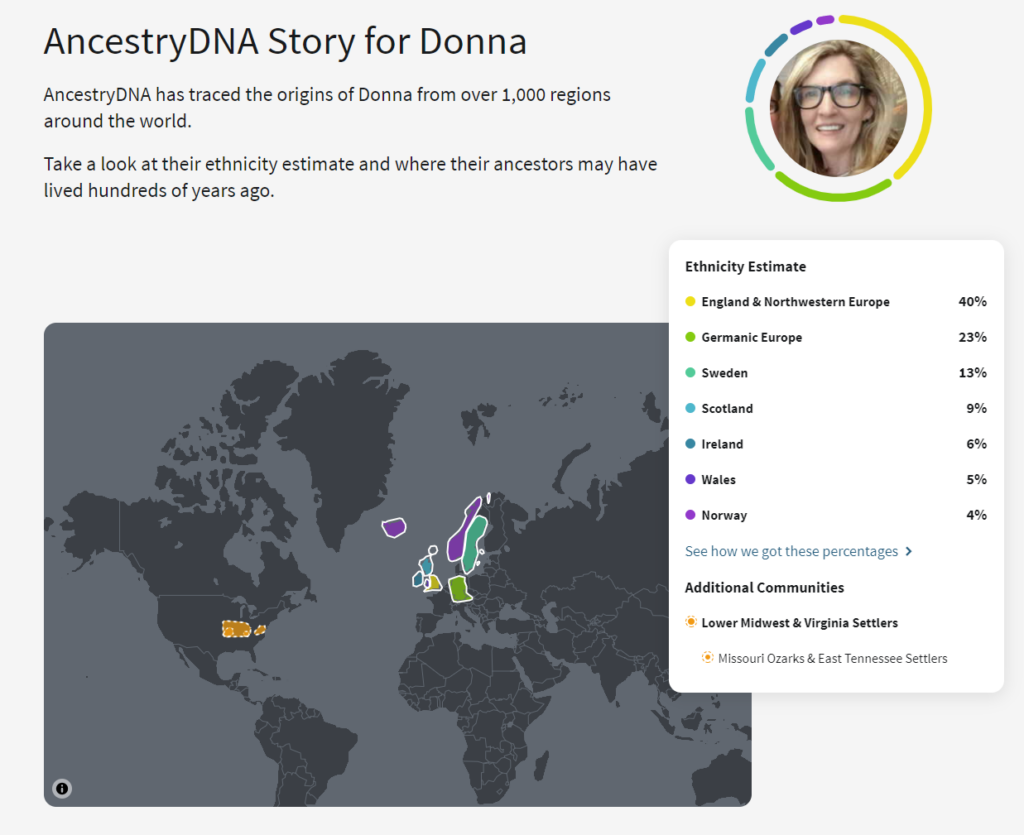

Not that long ago, I believed with all of my being that my heritage was German, Swedish and French, and that my great-grandmother was a Cherokee princess descended from Pocahontas. When my son, who rarely displays an interest in anything besides video games, said he’d like to take a DNA test, I agreed. Always good to encourage the kiddo’s interest, and his father’s Baltic and Native American roots were likely to be much more interesting than mine.

So we all took swabs — Caleb, my parents and I — and waited for the results.

A few weeks later, my beliefs crumbled. I’m British? I’m not Native American? This couldn’t be right! This test must be a joke. (Caleb’s results came back largely as expected, although he didn’t have any Native American in his admixture either.)

Determined to prove that I knew more than a silly blood test, I signed up for a trial of Ancestry.

Three days and 72 sleepless hours later, I had close to a thousand people in my tree. I was descended from Kings and Queens! I am ROYALTY! I hadn’t yet learned about source documentation, and didn’t know that other trees were often inaccurate. I cut and pasted and connected and found out that what I thought I was didn’t matter at all because what I am is REALLY important. My German and Swedish ancestry (which did show up in my admixture) was a “brick walls,” a term I quickly learned and rue to this day.

As it turned out, much of that original research was incorrect, and several years later, I’m still finding my own errors.

But what do you know? I’m western European, mostly British. I really am. The vast majority of my ancestors immigrated to the United States in the 17th and 18th centuries. I’d heard my mother speak of theTrigg family, and it quickly showed up in my tree. A US Congressman? A friend of Thomas Jefferson? She never told me that! My paternal grandfather’s family was early Dutch settlers of New York, the Wynkoops. I always thought he was 100% German, and his father’s family was indeed German, immigrated in the mid-1800s, but all records stopped on this side of the pond. Similar with my Swedish great-great-grandfather, whose census records variously claim he came over in 1852 or 1849, and that his name was Johnson or Johansson or Swanson or Svensson, documentation that I can begins in the United States. The lesson there — I had believed in the heritage of my most recent immigrants, whose heritage was known. But once the veil was lifted, there was far more British and Irish than I would ever have believed had I not discovered it myself. Notable is that I have only two immigrant ancestors who arrived after 1800. While not exactly a blueblood, my family has its roots in colonial America, I’m largely a Virginian, and daughter of the American Revolution at least a dozen times over.

As for the Native American, my mother to this day tells people she is descended from Cherokee royalty. But it’s just not there.

Many years later, genealogy has become my passion. I’ve travelled the US seeking information in dusty courthouses and remote genealogy rooms. I’ve made one the best friends of my life; and, yes, she’s a cousin. It doesn’t matter where I came from, but rather what I came from. I’m a Southerner, and a Quaker, and a compilation of all those who preceded me. I am uniquely me because of them. So many family traditions make sense to me now. They didn’t appear in isolation; they came from where WE came from.

And I can still spend three sleepless days at my computer seeking out more information about my family, only now I’m devoted to accuracy.

.

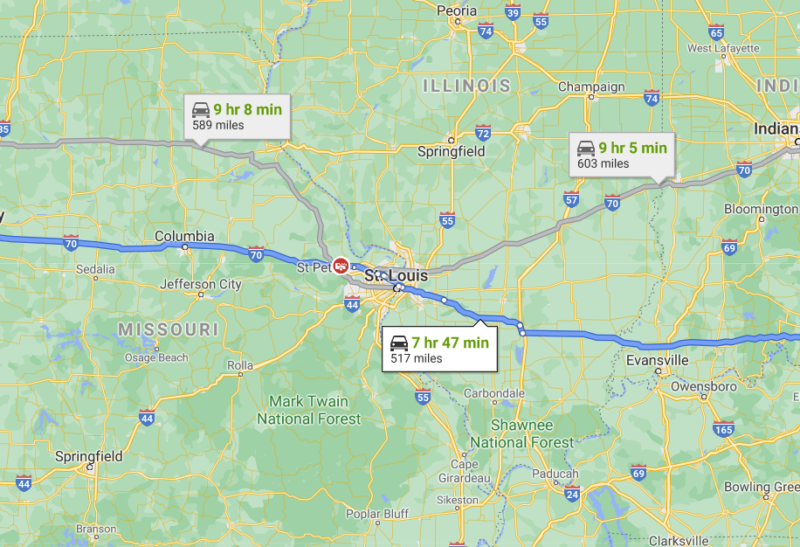

Kentucky Day 1: Kansas City to Louisville

Bags packed and ready for an adventure, Kim and I left Lake Tapawingo around 11 AM and headed east toward Louisville. Four months into the pandemic, family and friends questioned the sanity of traveling, but we'd missed our Paris trip and promised we'd be careful, social distant, masked, away from crowds. Travelling with Kim is a pleasure; eight hours of road time passed quickly, as we drove through Illinois, a bit of Indiana and finally arrived in Louisville.

We were both excited. Due to the prevalence of the coronavirus, we were able to use Hilton Honors to score free hotel rooms for very few points, and with gas at less than $2 per gallon, this trip was virtually gratis.

We were particularly excited about our stay in Louisville. The historic Seelbach Hotel, former haunting ground of the late, great, F. Scott Fitzgerald, was available at the same rate as a suburban Hampton Inn. Score!

Louisville was also an important stop on our ancestral journey: Simeon Moore, our 5th ggf had been one of the founders of Louisville in 1789. His name appears as one of the original Trustees, and we had located his original plot, one of only a hundred, at the current site of the Kentucky Science Museum.

As soon as we arrived in Louisville, we knew why we'd been able to score the Seelbach at the lowest tier of Hilton point. The hotel is located in the heart of downtown, just half a block from the entertainment district, but we quickly noticed the boarded up storefronts, broken windows and empty streets, other than a heavily armed police presence. What on earth was going on?

Breonna Taylor. I'm going to try to avoiding opining on the situation, other than to say the killing of Breonna Taylor followed a pattern of police aggression toward people of color that became glaringly public during 2020. On March 13, plain-clothed law enforcement executed a no-knock search warrant at Taylor's residence for a person not presently residing there, Taylor's boyfriend shot at the intruders, hitting one officer in the knee, because he feared he and Taylor were being attacked. In the melee that ensued, police shot into the apartment 36 times, unloading five or six shells into Breonna, killing her. There are some allegedly "extenuating" circumstances: the person for whom the warrant was issued had used Taylor's address to receive (what the police said were) suspicious packages. Without commenting on specifics, I will say that I believe no-knock warrants are rarely warranted, but never having served in law enforcement, I cannot say they are never warranted. In this case, its use was ill-advised at best and Taylor's death was absolutely unnecessary. I understand why people were pissed.

That anger led to nationwide protests, including one in Lousville on July 25. The day before we arrived, in the block on which the Seelbach stood, thousands of protesters had taken to the streets.

We arrived to survey the aftermath. Downtown Louisville looked like a war zone. While I do not condone rioting and violence for any reason, I understand that the damages were caused by a fringe element. The vast majority of the protesters were exercising their First Amendment right to peaceably gather.

The Seebach was, nonetheless, very beautiful. Stepping across its threshold was like walking into another era, and another world. Decorated in high art deco style, it felt miles away from the street outside.

We settled into our room and decided to get a bite to eat. We walked to the entertainment district. Everything was closed. We finally stepped into the Sport & Social Club, had a few drinks and some great food, and went directly back to the Seelbach. We decided to forego seeing Louisville and head directly the next morning to our next destination.

Just like us, Simeon didn't stay in Lousiville for long. He headed to the broader plains of Mercer County, along with his friend and brother-in-law James Harrod. We'll be there in a few days.

Will the Real John Green Please Stand Up?

John Green is the brick wall that won’t crumble.

I had to known down a few to get to him . I should say “we” knocked them down because it’s been a team endeavor. Dr. Watson — or perhaps she’s Sherlock to my Watson — is cousin Kim. Since we first solved the mystery of Lucy Green, we’ve worked our way through her father Erasmus to get to her grandfather, John Green. Or at least we think he’s her grandfather!

This is what we know with certainly: Lucy Green was born to Catharine Jane Moore and Erasmus “E.H.” “Bub” Green on August 22, 1955, in Kingston, Caldwell County, Missouri. Her parents had moved to Missouri in 1855 from Kentucky after having received a U.S. Land Grant. Lucy was the seventh of nine children born to Catharine and Erasmus, and the first born in Missouri. In 1861, Catharine died in childbirth when Lucy was just six years old. Erasmus quickly remarried the widow Virinda Joiner, who left her three boys with her brother-in-law and moved in with the Green family. Erasmus and Virinda soon had another child, Larkin. Erasmus lived until 1880 when he died in Ray County, Missouri (which had been carved out of Caldwell in 1836), with zero assets. His land had either been transferred or foreclosed upon by the bank.

Erasmus and Catharine had married in Mercer County, Kentucky, in 1837, when she was 16 years old, shortly after the death of Catharine’s father, John Moore. John had been a farmer of some substance, and a Revolutionary War veteran. His father Simeon Moore was one of the founders of Louisville and Harroldsville with his brother-in-law James Harrod, who was married to Simeon’s sister Sara. After John’s death, Catharine’s mother, Sarah Moore,consented to the marriage. Erasmus filed guardianship papers with the probate court so that Catharine’s share of the estate would be paid to him. (Based on what we know, Kim and I are not fans of Erasmus.)

The Moore family’s US heritage is well established, but not so with Erasmus’s.

In 1850, Erasmus is listed as a farmer and merchant in Owen County, Kentucky. There exists a license for E.H. and Paschal Green, and Josiah Moore (Catharine’s older brother), to run a tavern in New Liberty, Owen County, Since Erasmus is know to use the moniker “E.H.” and he lived in Owen County, Kentucky, we will presume that Paschale and Erasmus are brothers. Tracing Paschale is not difficult — born in 1799, he is listed in the Kentucky Biographical Dictionary of 1896 (hereafter “KBD”), after his death but at least during the same century. He married Agnes Blanton, a cousin to the famous Albert Blanton of Buffalo Trace Distillery, and was a Mason of high rank. According to the KBD, Pascal’s parents were John Green and Anna Rhoderfer, both born in Culpeper Virginia and married in 1796. John Green died in Owen County, Kentucky, in 1817, after Erasmus was born in 1812. DNA further suggests that Paschale is Erasmus’s brother, as both Kim and I share significant DNA with Paschale’s confirmed descendants, and other known siblings of this Green family. This leads us to believe with some certainty that John Green is thus Erasmus’s father.

Sounds simple enough, except there were at least a dozen John Greens living in Virginia in the late 1770s. Some are descended from one Robert Duff Green who came to the United States from Scotland in 1712, at the age of 17. Robert had seven sons, many of whom had sons named John, who also had sons named John. All of the Green progeny were tall and red-headed, and were called the “Red Greens.” There are several notable John Greens of the era. Colonel John Green led the Virginia militia from Culpeper during the Revolutionary War. His remains were reinterred as one of only twelve Revolutionary soldiers at Arlington. Colonel John Green’s son, Lt. John Green, was killed in a duel at Valley Forge. None of these are my John Green, and of all the Green family genealogies and written family trees, this John Green just doesn’t fit. I went to Culpeper early in my genealogy journeys, and there were Greens everywhere. As for Erasmus’s mother Anne or Anna, her name is the perfect example of the fluidity of early American names. It is variously spelled as Rodifer, Rhodefer, Rhodifer, Rhodeheifer, Rhoderfer and probably a few others I’ve forgotten. While the KBD says her birthplace is Culpeper, I believe she was likely born in the Shenandoah Valley, where the family is well established, or Madison County, Virginia, which was carved out of Culpeper County in 1792. \Their marriage certificate was issued in Madison County, Virginia, in 1796, and the 1810 census lists a John Green in Madison, Virginia, with six children, which is roughly equivalent to the older siblings Erasmus had.

In any event, Madison was apparently still considered Culpeper during this era, but it is undetermined whether our John Green belongs to the prominent Culpeper Red Greens, or if he is unrelated.

On top of all of this, another John Green lived in Kentucky as early as 1800, and many of the trees on the internet have conflated even the Kentucky Green families.

So, who is John Green? Kim and I decided that we had to go to Kentucky to see if we could find our John, and any information as to his provenance. While we were there, we would go to Mercer County and walk in the footsteps of the Moore family.

Cousin Kim

Kim is one of my dearest friends, and my cousin. We might never have met if not for Ancestry.

I took a DNA test hoping to learn more about my maternal great-great-grandmother Lucy Green. When I received my results, I logged onto Ancestry.com and found a “Lucy Green DNA Circle” that included just my mother, Kim and me. I messaged Kim and learned she was similarly obsessed with solving the ancestral mystery of Lucy.

We lived near each other! We met at a local genealogical library and started digging, becoming fast friends. Thread by thread, we found Lucy’s mother Catharine Moore, born in Kentucky and settled in the Missouri territory under land grant.

Another Ancestry.com member provided documents obtained over thirty years of footwork, before the Internet made it easier. Catharine’s father, John Moore, grew up in the wilderness of Pennsylvania, where the family lived in constant threat of attack by the Natives. John’s father, Simeon Moore, moved his family to safety in Kentucky, where he helped settle Louisville.

John Moore’s American Revolution pension application notes that he was captured by the Redcoats and kept prisoner for three years to interpret the Native languages he had learned as a child.

Our trail thus far ends with Simeon’s father, George Moore. We believe George immigrated from Antrim, Ireland, but documentation is probably buried in a dusty parish on the Emerald Isle, waiting for us. We’re certain that the rest of the story of these brave pioneers must be just as fascinating as the chapters we have unearthed over the past two years.